Lost trails, smoke, and solitude

I finished the last long switchback to crest of Sleeping Deer Mountain. For past two days I had trudged up hot side slopes, clambered over logs, and fought chest-high brush in wet bogs, the 9,881-foot white granite peak in my sights. The Forest Service reported that trail was cleared in July 2015 but it seemed little cutting of newly fallen logs and vegetation.

Topping the ridge, I expected a panorama of the Salmon River Mountains—a rugged range above the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, our fifth range in a trek through central Idaho. At 275 miles, we were three weeks into our trip.

Harsh winds met me. Smoke filled the valleys in every direction. David caught up; we decided to skip the steep one-mile trail to Sleeping Deer Lookout perched on the white ridge above.

Our Idaho revisit (also described in newspaper) was marked by dry days, dead trees, and fire effects—old and recent.

Eroded trails, down logs and vegetation, barren flats, cool old-growth forests replaced by black poles, and fish-poor lakes indicated the hiking paradise we remembered was no more.

After years on the East Coast, we had moved back to the West. Idaho native David planned a homecoming trip to link favorite places—most now wilderness. We’d hike from our neighborhood in Hailey all the way to the Bighorn Crags in the Frank Church—where we would meet a friend from Salmon and get a ride home.

For our hike from Hailey via route, roads and trails across the Pioneers, we had cool and cloudy weather. Climbing to Pioneer Cabin, showers required raingear. Then rain quit for three weeks, while increasingly smoky skies underscored the ongoing impacts of fire in Idaho.

Although we miraculously kept to our itinerary, we were challenged by heavily burned trails, while an ongoing family emergency amplified the downside of remote hiking.

show more

Pioneers & Boulders: fire impacts & bad news

We had checked out routes across the trailless Pioneers and Boulders before our trip, so our first few days from the house went fairly smoothly. However, David’s back hurt his back on after our ambitious 21-mile first day aimed to camp on national forest land (we made it, right at dark!). He took it easy the next two shorter days on trail and game routes.

In the Boulders we contoured down goat path into East Fork Big Wood River, finding an old trail at the bottom of the basin mostly obscured by down logs—our first of many encounters with fire effects. Worn from this venture, we passed up a possible short cut (pretty obscure but marked by a blaze and a camp) to West Pass and took a long, hot roundabout route by trail and North Fork Road, climbing the steep trail to 10,030-foot West Pass the next morning.

On the pass, I pulled out my cell phone to take a photo for our daughter Michal who lived on the East Coast with husband Corentin. A voicemail from Michal: please call asap.

Michal was in the hospital. During her bicycle commute to work, she was hit by a vehicle in a cross-walk and now had shattered ribs, broken scapula, and a collapsed lung. I frantically did the math: days to hike out, get a ride from remote Smiley Creek (taxi? Uber?), flying to Baltimore. She read my mind. “No Mom. This is your trip of a lifetime. Corentin is here. I am fine.”

She talked me out of it. However, for the rest of trip, on every ridge top and every layover I tried frantically to keep in touch with my broken daughter in Maryland. The only time I regretted not owning a satellite phone. Smiley Creek’s landline, the Stanley hotel’s satellite phone, text exchange on high ridge in the Salmon River mountains, using the staff Wi-Fi for long text exchange at a lodge on the Middle Fork of the Salmon—I followed her surgery (ribs plated with titanium plates to save her lungs), recovery, and return home (to the care of her mother-in-law) while I hiked, checked in, and felt guilty.

White Clouds: boyhood dreams revised

We had included a jaunt through the White Clouds—just designated wilderness, David’s favorite place since a teen fishing trip and an area we had backpacked many times. A steep climb to Chamberlain Basin, over pass by famous Castle Peak, down to Boulder Creek and up a “social trail” we recalled into the lakes basin that used to be quite good. But the route was clogged with large down trees killed by bark beetle; we got to Noisy Lake at dark.

Original plan was to go all the way up adjacent Boulder Basin, over Windy Devil Pass and scree route down to Born Lake, then across pass to 4th of July Lake and on to Washington Basin, but we were short on time so instead backtracked to Chamberlain Lake the next day, finding only a tiny ledge to camp with hordes occupying dozens of sites on the lower and upper lake. The bright spot was large cutthroat trout David caught, augmenting minimal freeze-dry cuisine.

Next was to be a highlight: camping at Upper Champion Lake. David’s first mountain lake basin fishing experience was at Lower Champion just below, severely burned in the Valley Road Fire of 2005. The Washington Basin road was cherry stem—exempted from wilderness—so we plodded up as Universal Terrain Vehicles poured down the newly-graded dusty road out of the basin. Passing old cabin and mine ruins, we took the ridiculously steep trail over the ridge and dropped into Champion Lakes for wonderful solitude—but no fish either due to aforementioned fire or low-oxygen winter kill (we later talked to Idaho Fish and Game—they were surprised to hear of no fish).

Sawtooths: Smoky Skies, Dust & Crowds

Our foretaste of fire problems came during first layover at Smiley Creek—132 miles and 10 days in. We saw smoke creeping into the far north end of the valley while dining on outside patio. The Pioneer Fire had started in nearby Boise National Forest and was smoking up the Payette River drainages. Our Sawtooth crossing alternated between daytime bluebird skies, and evenings where alpine lakes glowed red from smoky-sky enhanced sunsets; with dusty-deep dry trails hammered by heavy horse and hiker use.

We saw dozens of backpackers and played “hopscotch” the first day with what appeared to be a day hiker group; late in afternoon we were overtaken by a packer with string of horses carrying their gear to Edna Lake. The excellent trails reengineered in the 1960s were still fair except clogged by post-fire brush (from a 1980s fire) on descent from Baron Lakes and up North Fork Payette Trail to Sawtooth Lake; some bog bridges were flooded due to minimal maintenance.

We left Sawtooth throngs to contour around the beautiful but heavily used “trailless” Goat Lake basin, camp on the edge of national forest and make our way on roads through a private ranch (with an incredible view of Goat Falls), relieved to not be challenged by the landowner.

Salmon River Mountains: lost legacy, blackened basins

Stanley was cloaked in smoke. After layover there we walked and hitched rides on Highway 21 to Beaver Creek Trailhead, launch for our fourth segment within the 2.3-million-acre Frank Church wilderness. We would pass through Salmon River Mountains climbing and dropping thousands of feet across steep ridges and big creeks flowing to the Middle Fork of the Salmon River (Middle Fork). Fire effects—we crossed recovering landscapes from at least 7 fires (1979 to 2012) in the Frank Church—dominated this part of our trip.

Absentee Landlord: In the Frank Church, we passed by two lookouts (fire towers or huts on a peak, once used by Forest Service to spot fires before newer technology air flights) and three administrative compounds —all closed. (An air strip facility on the Middle Fork we passed is still in use). A Challis National Forest historic compilation listed more than 30 administrative sites plus backcountry ranger stations and other lookouts active 1930-1970s. When national forests were created at turn of 20th century, the Forest Service moved into the backcountry, building or buying facilities, and extending old mining/livestock/wildlife trails for its own work. The compilation noted 1,200 miles of trails maintained in 1964. (Salmon-Challis website reports “100s of miles” of trail but says many in poor shape. The Middle Fork Ranger District maintained 271 miles in 2019.)

Funding cuts and laws requiring more environmental analysis prompted office consolidations and moved staff back to town to “ride desks rather than horses,” as locals told me in the 1980s. Closed facilities in the Frank Church may help explain poorer trails; although the Salmon-Challis National Forest (merged in 1996) has a more active trail program than most forests, it no longer staffs the backcountry or uses many trails. Unlike the previous era, there is much less incentive to keep up trails for its core mission. Besides this, much Frank Church acreage has burned over the last 40 years; creating a moving target hard to keep up with because forest/brush regrowth is very dynamic after severe fire and dead trees periodically fall for decades. For us this meant slow going around obstacles and route finding where trails tread gone. (I further describe this overall problem of trail loss in Western wilderness in a recent blog ).

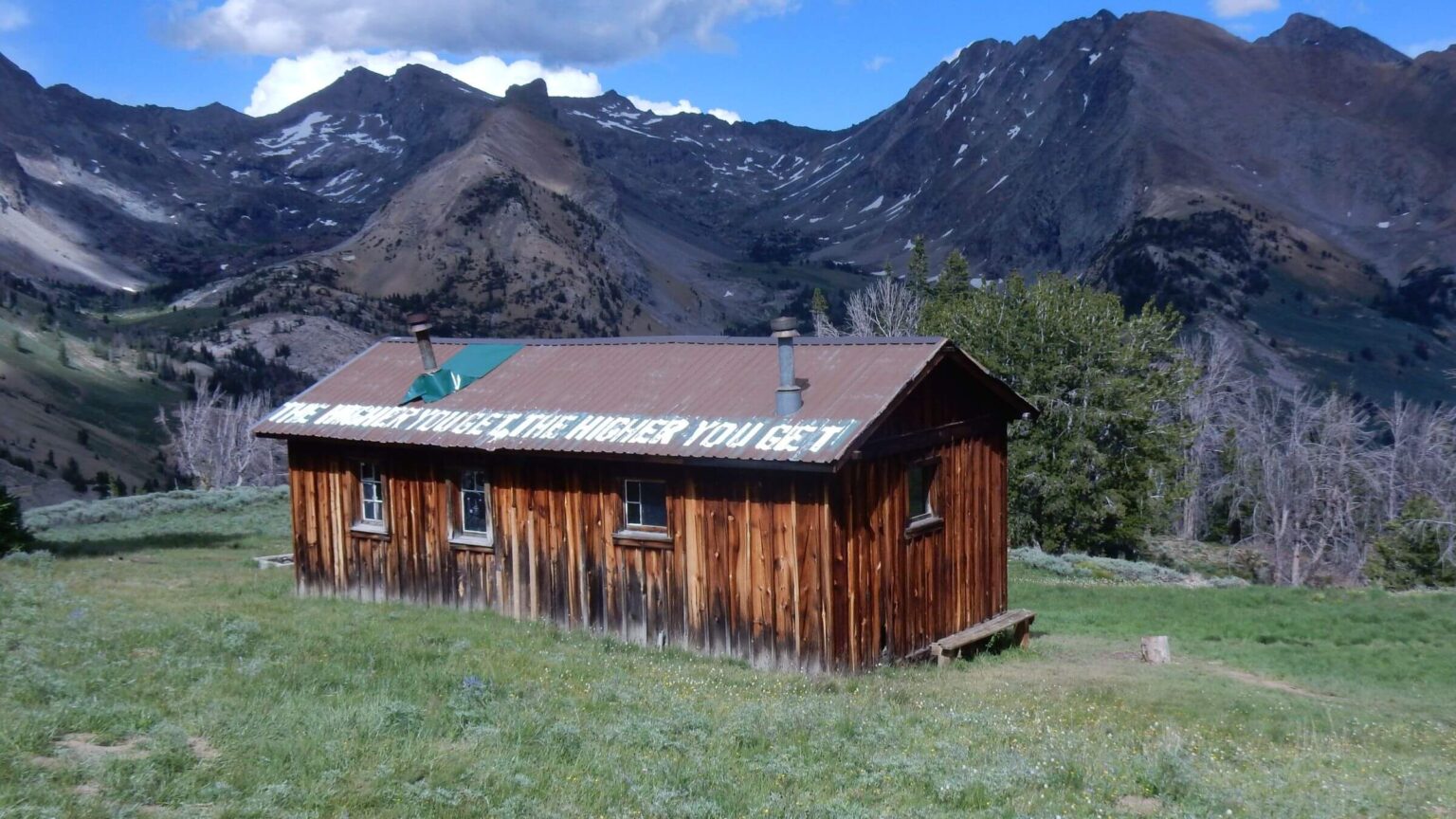

Hiking through big burn: Our three-day journey through impacts of 2012 Halstead Fire (which burned 182,000 acres, the largest so far on our hike) began at a nice trailhead sign that neglected to mention the trail had been rerouted! Trail soon disappeared in boggy meadows and downed logs until we found it coming in from reroute. We climbed steeply through post-fire lupine carpets and crept along thin ridge contour with views back to Sawtooths and White Clouds and smoke filtering up drainages; then Roughneck Lookout, preserved from the fire but closed with weathered paint. We dropped down cross country and camped by a fringe of trees along Island Lake. Years ago, David had briskly hiked good trail in a few hours; after our morning highway hike and hitch, the hike took us until after dark.

Next day we hiked through blackened tree skeletons and moonscape lake basins, but like phoenix out of the ashes were monkey-flower, penstemon, fireweed, Indian paintbrush, and several shrubs. We passed shimmering blue lakes shining through grey trees above Fall Creek, and slid down eroded steep jeep road to Seafoam Lake—where we met a dazed couple who had driven up on All Terrain Vehicles, shocked that their favorite paradise camp had burned. David, far ahead of me skittering down slick switchbacks, saw a small head pop up as he went to filter water from a creek. The weasel flashed into the bush before he could find his camera. At the bottom of the basin, fire crews had saved forest around the closed large Seafoam Guard Station complex.

Missed Reroute: The 1979 Mortar Fire produced the worst part of the trip. After steep road to Sheep Mountain (now bare of its fire lookout) we hiked ridge trail with views of rocky peaks. At a boggy saddle, we dropped into Little Loon Creek burned in 1979. A new sign on burned tree, “Middle Fork Salmon River” apparently indicated a trail reroute on the ridge but we missed the point and took the obvious trail (also shown on our GPS map) into the head of Little Loon.

All afternoon and next morning, we clambered over logs and hacked through shrub jungles in the creek drainage at a stunning quarter mile per hour pace—until we met newer trail dropping steeply off the ridge south of us (later Google Earth examination showed a 6-7 mile route on ridge). Only then did we realize the sign we had seen indicated a rerouted ridge route and abandoned creek trail.

Closed historic sites and blackened ridges: After historic Fur Farm site, we saw horse tracks heading on down Little Loon Creek towards Middle Fork. We turned off up Castle Creek towards Cougar Lookout ridge burned in 2012 Merino Fire. I missed a switchback in downed trees and by the time David (who had stopped to pump water) caught up with me, it made more sense to hike straight up a swale rejoining trail on blackened ridge and making camp at sunset. Next day we met old road that passed the closed Indian Springs Guard Station, made long switchbacks into Jack Creek, and descended to river-sized Loon Creek on a blazing 100-degree day. We checked out Falconberry Guard Station, another unoccupied facility, before welcome bridge across the big creek and our long climb up to Sleeping Deer.

A cherry-stemmed spur road that extended 26 miles into the wilderness ended just below Sleeping Deer saddle, so we weren’t surprised to see our first backpackers since Roughneck Lakes in the Cache Lakes basin below. We left people again, climbing to Wood Tick Summit through an old fire that was reburned by 2007 Red Bluff fire, and following ridge down to camp among white snags and logs at Grouse Lake. The next morning we connected with ridge trail from Martin Mountain that was fair until the 5000-foot plunge to the Middle Fork.

Into the Middle Fork: As we entered a meadow, the main trail users—elk—had scattered into several routes. David insisted on following GPS route—on no trail at all—and I argued for the most promising elk route. He won the spat by insisting that GPS route at least followed the former (unmaintained) trail. After several more or less trailless miles slowly descending on ridge and valleys, we found switchbacks for last drop to the river (area later burned in 2017 Tappan fire) and joined the well-built Middle Fork Trail.

We crossed Camas Creek, earning curious stares from a dozen rafters camped there. As the only hikers on the Middle Fork, we would intrigue multiple rafters over next few days—eliciting food offers, beer, and questions on our trek itinerary. After a pleasant night under ponderosa pine on river bar, we hustled six miles trail on mission: get to Flying B Ranch in time for lunch. We were rewarded with homemade clam chowder, cold cuts and bread, and fresh-squeezed lemon-aid.

During our trip we had kept our packs light but ate hearty on layover days. We had resupplied four times—a bear bag hung off trail near Trail Creek Summit, boxes left at Smiley Creek and Stanley, and a box mailed to Salmon and flown to the Flying B, private inholding on Middle Fork accessible by aircraft, boat, horse, or foot. It’s owned by 150 members: many of them pilots. It’s also open to paying guests, some who fly in for breakfast. Rafters also stop here for beer and ice cream. We ate 4 meals at Flying B before we continued our hike.

Frank Church: Cloudy Cool (Bighorn) Crags

Drought ended abruptly on the Middle Fork. Camped on a sandbar downriver from Flying B, we awoke to pelting rain. The next two days we met periodic thunderstorms along the river and up heavily burned Waterfall Canyon into the Bighorn Crags. Trail damage made for slow going. Years before we had camped on Heart Lake on other side of a pass and I jogged what then was excellent trail through old growth conifer partway to the river and back. Now the barren, brushy, log-jam trail took us nearly two days to reach lake basins and good trails of the Crags.

We met friends from Salmon area at Birdbill Lake, a basin framed by Fishfin Ridge and base for hikes to trailless basins and famous Island Lake (where a waterfall descends 3000 feet to the Middle Fork). An outfitter packed in our friends’ gear plus steak, hamburgers, salmon, bacon, eggs, bread, PBJ, fresh blueberries, beer, and chocolate they bought for us. An extra mule had been hired to pack out our backpacks. On the 32nd day we hiked to Crags Campground with only hiking staffs. Despite this cushy ending, David, and I each weighed in 10 pounds lighter.

Our days above timberline in the stark, scenic Crags were cool and windy. Rain just threatened with little impact on fires. The Roaring Fire in the Bighorn Craigs over the next major ridge a few miles north and other fires added new colors to the sunsets reflecting in the mountain lakes. The Pioneer Fire 60 miles southwest was not fully contained until November at almost 190,000 acres after heavy fall rains.

Would we do this trip again? Probably not. Many landscapes were stunning but fire-damaged neglected trails were too frustrating and slow for a continuous trek.

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking right arrow down/up.)

Downloads

Links

- Sun Valley Trail Map: Pioneers and Boulders

- Forest Service: Boulders, Sawtooths, and White Clouds maps

- Forest Service: Frank Church map purchase ($14)

- Forest Service: Middle Fork Ranger District trails

- Forest Service: Salmon-Challis National Forest trails

- Idaho Centennial Trail

- Forest Service: Salmon-Challis historical facilities