70-mile Ramble Celebrates Milestone Birthday

Since we have concluded we “need wilderness,” once we settled for our first full winter in Tucson, David was anxious to hit the trail, not having backpacked since September.

Cindy—temporarily derailed from backpacking after a knee replacement—suggested a 70-mile solo trip to celebrate his 70th birthday November 28, 2021.

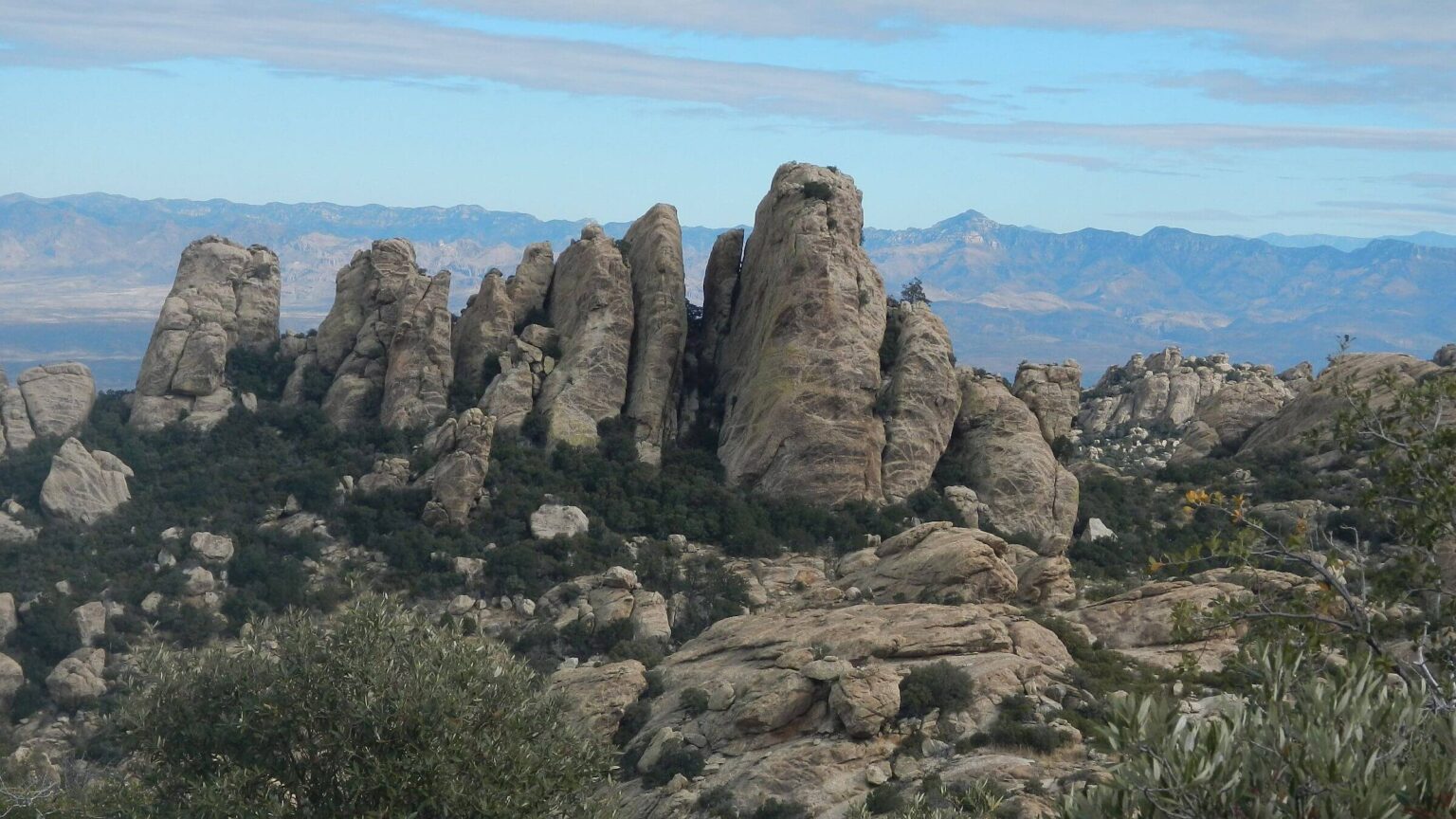

He chose the familiar Rincon Mountains east of Tucson with their large trail system; most well-maintained. Although we have visited the Rincons many times, this trip would GPS map the remaining trails not included on our Saguaro and Catalina-Rincon visits.

Cindy dropped David off around 8 a.m. Sunday, December 5 at Douglas Springs Trailhead, his favorite trailhead from University of Arizona days in late 70s—a straight shot from campus to end of East Speedway. The then-desolate trailhead on national forest today is very popular, as it provides “free” access to nearby trails in Saguaro National Park/Wilderness, a fee area with visitor center access.

David planned a 70-mile loop around the Rincons, hiking trails in Saguaro Wilderness managed by National Park Service and in adjacent Rincon Wilderness managed by Forest Service, then finishing the trek on non-wilderness section of Arizona Trail (AZT) across Redington Pass between the Rincons and the Santa Catalina mountains to the northwest.

On the six-day trip, David exceeded his mileage goal a bit, did all trails in Rincon Wilderness, and hiked the one trail he had never visited in the Saguaro Wilderness. He also had a late-night surprise from the Park Service and found out he was overall a bit slower than planned.

Interestingly, he found the upper reaches of Saguaro Wilderness—despite many day hikers in lower areas—were lightly used in the winter except for a few weekend backcountry campers and southbound (SOBO) AZT thru-hikers nearing Mexico.

Rincon Mountain Wilderness, nearly 37,000 acres, surrounds about 60,000 acres of Saguaro Wilderness (eastern unit) just east of Tucson in the Rincon Mountains. “Rincon” is Spanish for “corner”—apparently referring to the southeast corner of mountains (Mica, Tanque Verde & Rincon peaks) east of Tucson.

Wilderness was designated in 1976 for Saguaro (managed by National Park Service) and in 1984 for Rincon Mountain (managed by USDA Forest Service). The Rincon wilderness is largely trailless, except for some of the Arizona Trail (AZT) and small parts of Miller Canyon and Turkey Creek Trail passing through en route to Saguaro, which has most of the trail system.

This odd arrangement of two adjoining wilderness areas managed by two entities in the same mountain range happened because Saguaro National Monument was carved out of the Coronado National Forest in 1933 (to protect saguaro cactus), later transferred to Park Service administration, and eventually upgraded to National Park.

Trip was designed to celebrate David’s 70th birthday (Cindy was still recovering from knee surgery). He started from his favorite trailhead at eastern end of Speedway Blvd from university days as a member of the UA Ramblers hiking club. He mapped out 70-mile route designed to hike all the trails in Rincon Mountain Wilderness, hike the North Slope Trail (only trail in these mountains he had never hiked), and end up by a road (for pickup) at about 70 miles.

Visit statistics: 6 days, 73 miles at 1.9 mph, with 525 feet per mile of average elevation change.

Go to map below for more information on trailheads, daily routes, mileages, elevation changes, and photos. (Click on white box in upper-right corner to expand map and show legend with NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS.)

show more

Rincons History

The Hohokam Native Americans first utilized the Rincon mountains. TheiThe Hohokam Native Americans first utilized the Rincon Mountains. Their descendants (today’s Tohono O’odham and Pima) may have called the Rincons “Cew Do’ag.” One source says this name related to mountains in O’odham and that several O’odham words for “corner” start with “Cu,” so “Cew” might be a phonetic spelling. It is not in the O’odham-English dictionary. “Rincon” is “corner” in Spanish.The entire area was reserved from public lands in 1902 as the Santa Catalina Forest Reserve managed by the Forest Service. Southern Arizona forest reserves were later consolidated as Coronado National Forest, named for Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado.

Part of the Rincons were carved out of national forest in 1933 to form Saguaro National Monument, in response to local requests to protect giant Saguaro cactus on front range of the Rincons. Monument management was transferred to Park Service two months later. Saguaro Wilderness was established in 1976 and the monument upgraded to national park in 1994.

Once private ranchland, Rincon Valley inside the Rincon “corner” is now being converted to tract housing, which unfortunately blocks access to part of the Rincon trail system. Cattle ranching continues east and north in Rincon Wilderness, in non-wilderness forest and on private land.

Forest Service and Park Service manage wilderness differently. Forest Service usually acknowledges wilderness with entry signs but has few restrictions on visitor numbers and campsites except in heavily used areas. Park Service has many rules. In Saguaro Wilderness, backpackers must camp in one of six campsites and get advance reservations online. Interestingly, Park Service doesn’t mention wilderness on its website or on any signs.

When David reserved campsites for his trip, he was surprised that a planned campsite, Spud Rock, was only available on alternate weeks. He planned his itinerary around this with four camps in official Saguaro campsites and one on national forest along the Arizona Trail, where no permits or reservations are required.

Crowded parking lot, few on the mountain

On Day1, David met an inquisitive fellow at the trailhead who introduced himself as a Park Service volunteer. “Do you have a permit?” he asked. Yes, David did. “Where are you going? Are you camping at Grass Shack?” In printing his permit, David had noticed that campsite was closed due to mountain lion activity, and said, “No, I am not doing the mountain lion camp.” His first night would be at Manning Camp near the top of Mica Mountain and best source for reliable water. He asked about water at Happy Valley, his second campsite. The volunteer did not know.The parking lot was almost full (and David knew from past visits that it would fill up with more cars parked along Speedway by mid-morning). But he met just a few people between the trailhead and Douglas Springs Camp 4.2 miles away: a backpacker group on the way out, trail runners, day hikers visiting Bridal Wreath Falls (1.6 miles up the trail), two other groups, and a speedy day hiker who passed him. Before he reached Douglas camp, that hiker had returned from Cowhead Saddle, a 18-mile roundtrip from Speedway.

The rest of his trip David saw one camper, two SOBO Arizona Trail hikers, and a few people near trailheads. The main Rincon (Saguaro Wilderness) users hike the spaghetti maze of “day trails” between Speedway and Saguaro National Park; very few camp on top.

Ring Around the Rincons

On Day2, David hustled out of Manning and hurried down Heartbreak Ridge to Happy Valley Saddle, his next campsite, where he dropped his pack with hopes of summiting Rincon Peak. He found water in potholes just before the Rincon trail turnoff. He had to stop short of the peak to get back to camp before dark.Day3 was a loop to cover trail sections in east part of Rincon Wilderness. David descended Miller Canyon Trail. Coming up Turkey Creek Trail, he saw a day hiker who had turned around at the boundary between Saguaro and Rincon wilderness. He was “welcomed” by cattle, probably the biggest users of Rincon Wilderness.

Up trail a couple miles into Saguaro Wilderness (marked by sign as National Park but not as wilderness), he found signs of trail construction: rerouting and rock work for water bars (to mitigate trail erosion).

About sundown, David found a nice but illegal campsite; he pressed on. Arriving at Spud Rock well after dark, he found every marked site occupied by a tent (apparently all were snuggled in for the night). He dropped his pack, wandered around in search of an “illegal” site, and eventually made do by piling up pine needles to level a slight hillside.

Next morning, he saw that identical green tents at every tent pad in Spud Rock were unoccupied. A large white “kitchen and mess” tent at Site 1 in center of more green tents (one marked by an unofficial New England flag and gear hanging in trees) explained why the Spud Rock site was occupied so much in the online reservation system: a Park Service trail crew was using it, and didn’t bother to take down tents on sites open to public in between work shifts. Rude!

Now back on Mica Mountain, David dropped his pack at empty Manning Camp for a day hike. He circled Mica Mountain on a trail he had not hiked before: North Slope Trail through remnant mixed conifer largely burned in Helens 2 Fire of 2003, but including some nice remnant old-growth forest patches.

Stormy Departure On AZT

On Day4, David met his first backpacker since Day1—a southbound AZT hiker briskly hiking the 20 miles through Saguaro in one day to avoid dealing with Park Service camping reservations. He later met another AZT hiker—less ambitious—who planned to spend the night at Manning. A new Forest Service sign marked Rincon Mountain Wilderness boundary; Park Service’s nice trail signs never mentioned wilderness or backcountry.After 15 miles on AZT, David was still short of his planned camp at West Spring but had packed enough water for camp from Manning. With strong winds, clouds, and predicted rain, he stopped in Chimney Rock Creek tributary under shelter of a large juniper tree. Rain much of the night rewarded his choice.

Rain cleared at sunrise, leaving chilly temperatures, wind, foggy mist, and puddles enjoyed by doves. It was 5 miles to West Spring—David was glad he hadn’t pushed through. Just before the spring he met two mountain bikers.

A “no camping” sign on gate by Arizona Game & Fish just before West Spring did not deter the many cows who had “camped” there, leaving ample manure. The spring was just a trickle, although the rain had provided many pools in washes and rocks along the trail.

Just above the spring, David’s ride, Cindy, was making her way down the steep trail. About 2.5 miles from Molino Basin, his GPS marked 70 miles—he had underestimated the mileage a bit. He had also overestimated his hiking speed—David thought he would be faster hiking solo than with Cindy. Although he exceeded 2 mph on the AZT, his trip average was below that mark.

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking right arrow down/up.)

Downloads

Links

- Spring hiking in Rincons (maybe 2013 UA Ramblers)

- USGS link on real-time water availability,(if questions, email us)

- Trails Illustrated Map: Saguaro National Park