REVISIT: 38 Years Later, a Very Different Place

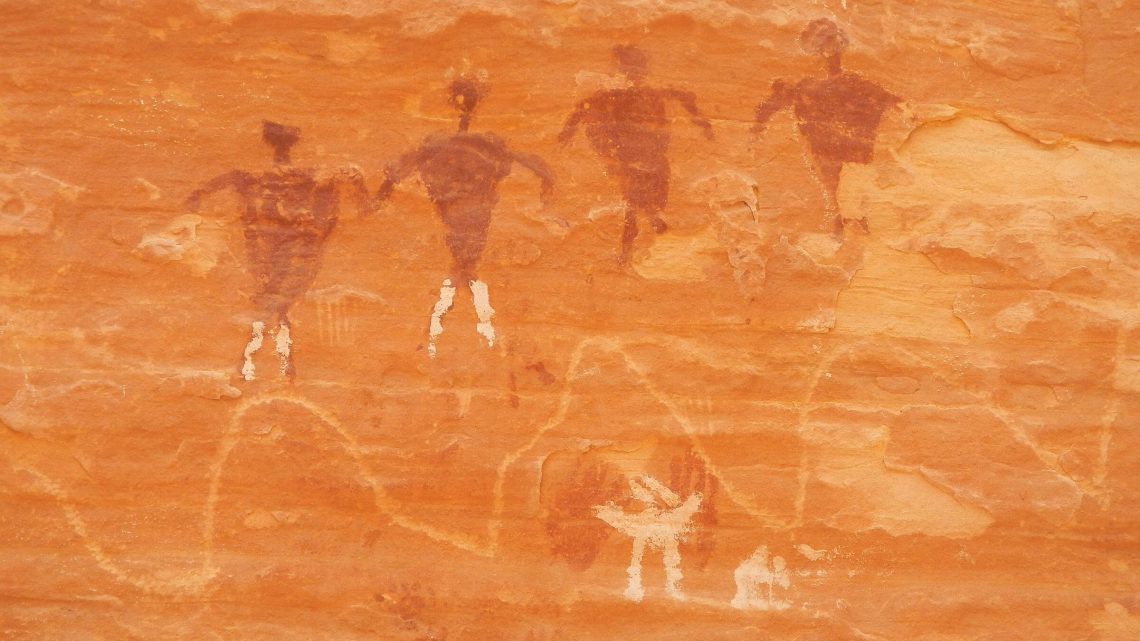

In April 1981 we hiked Grand Gulch—a long canyon in southern Utah known for cliff dwellings and artifacts—from Kane Gulch to the San Juan River. Photos and memories conjure up a hot hike slogging sand, minimal vegetation cutting across meanders; and petroglyphs, granaries and dwellings on east-facing alcoves; 800+-year-old traces of a people long gone. Showers late in the trip were welcome—cooling it down and offering better footing on wet sand.

In May 2019 we returned to a very different place. Only the ancient dwellings and drawings in alcoves above the Gulch remained the same.

The Gulch was a Primitive Area in 1981; now it has graduated to Wilderness Study Area. The Bureau of Management, which administers the Gulch as part of larger Cedar Mesa complex, has replaced its shabby trailer with a nice visitor center and a small cadre of staff/volunteers. It now requires a hiking permit (to limit numbers per day entering popular trailheads) and fee for backpacking but provides no restrictions or information on hiking the Gulch. We even met two wilderness rangers patrolling in the Gulch between Government and Collins.

But biggest change was the Gulch itself. In the upper reaches, the sandy wash was now a deep ditch filled with water, lined with invasive non-native salt cedar and sediment piled feet deep. This forced numerous crossings and treks across meandering flood-plain cloaked in non-native grasses and sometimes waist high curly dock. “Social trails” formed by hikers avoiding water made sharp drops 6-10 feet into the ditch. In some places, formerly verdant cottonwood trees were filled with tent caterpillar cocoons and leaves left with only spindly midrib and veins; rest consumed by pesky caterpillars that were falling everywhere from trees. This outbreak may have gone on several years because we saw many dead cottonwood (takes successive annual defoliations to kill a tree) and dead salt cedar (also favored by the pest) in some areas. Interestingly there seemed a lot of boxelder maple (not attacked)—particularly young—that were flourishing either due to changed water regime or resistance to tent caterpillar.

Grand Gulch Wilderness Study Area was revisited in May 2019 after an unusually wet spring.

Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) ruins abandoned about 13th century are best-known feature of this 52-mile canyon from Kane Gulch to San Juan River.

Planned 9-day trip to river & back to repeat first visit April 1981. However greatly altered stream channel, running water and dense vegetation slowed pace. Therefore, we hiked down Grand Gulch to The Narrows and back to the Government Trail where we left Grand Gulch to loop back to Kane Gulch, including a visit into Bullet Canyon. Then we drove to Collins Canyon Trailhead to hike down Grand Gulch as far as Red Man Canyon.

Poor planning information: On our changed itinerary, we learned from another hiker that we probably could have gone down entire Grand Gulch and looped back through Shangri-la Canyon near river, returning to Kane Gulch over mesa (as we did) in time we had available. BLM offers paper handout of overused Kane-Bullet loop but best information source is sorting through many personal websites (from internet searches) to accumulate disparate route data.

Visit statistics: 9 days, 109 miles at 175 feet per mile of average elevation change (but GPS data approximate because it does not work well in steep-walled canyons).

Go to map below for more information on trailheads, GPS routes, mileages, elevation changes, and photos. (Click on white box in upper right corner to expand map and show legend with NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS.)

show more

A wet winter and spring meant water running in much of the Gulch. After a day and half of grey skies and cold, rain settled in, creating waterfalls off canyon walls, rising water for difficult crossings and wet vegetation soaking boots, socks and feet despite raingear. Further down we found sections of sandy wash and less vegetation on the flood plain. But slow going thwarted plans to hike to river and back in 9 days. By day 4 we were only halfway. Time for change in plans.

We camped near Bannister Ruin, and hiked as far as the Narrows, a narrowing in the channel where two rock walls nearly meet, with two big logs jammed at 10 feet above wash. Apparently recent flooding created a lake that breached through the rock, creating new channel and cutting off a meander loop (now over 20 feet above the Gulch; the Collins trail confusingly follows this meander instead of dropping directly into Gulch).

We returned up the Gulch, took Government Trail to the mesa and looped back to Kane Gulch Ranger Station by mostly dirt roads, just under 2 miles of highway and Immigrant Trail. We made a short detour into Bullet Canyon by a side canyon with only a few pour-offs; and took a day hike to Jailhouse Ruin, which wasn’t quite worth the 1000-foot drop-off (for me) on a cairn-marked cliff, scramble down the creek bed and long hot lower sections. (On the way back up, I found a safer route, also marked, along the pour-off.)

Going back on the mesa was my idea. I refused to hike the ditch again. Ironically, when we backtracked to Government Trail for a rim route out, we met a guy coming down who said he planned to hike down the Gulch almost to the river and depart by “Shangri-La” Canyon—unnamed on our map but which he said was reasonable route climbing to flats to make one’s way back to Government trailhead. If we had known about that option, we would have done it.

Emerging at Kane Ranger Station, we drove around the Gulch and took Collins Trail—best trail in the area—back to the Gulch, camping in a white dry-grass alcove (the early maturing seeds of this non-native did not stick too badly to pants and tent). Next day we hiked as far as Red Man Canyon, hoping to see a red petroglyph we have a photo of from 1981. We did not find it. Looking at our 1981 photos, we later realized we also missed a couple arches and other dwellings we had seen in our earlier trip; the increased vegetation probably blocked views.

Most of the large groups we encountered were cheery despite rain and crossings; and ecstatic over the ruins, drawings and artifacts (which are impressive). Most were doing one way trips using a car switch—Kane to Bullet (or visa versa) seemed most popular, others headed to Collins Trail from some entry point. A few come up from the San Juan River using boats often furnished by an outfitter. Although we saw many tracks in Gulch below Government Trail, we met only one day hiker from Collins and the two rangers doing a vehicle switch; we camped alone.

Midway in the trip we chatted briefly with Vaughn Hadenfeld, owner of Far Out Expeditions from Bluff, camped at Polly’s Canyon with a group of clients (where Government Trail enters the Gulch). Hadenfeld, who has guided here 30 years, said yes there are more non-native plants invading and lots of floods. In a later phone interview, Hadenfeld attributed water flow in upper Grand Gulch to precipitation that was 200 percent of normal. He noted that the Gulch used to be grazed which probably meant less vegetation. (The cattle probably also brought seeds for today’s invasive grasses and weeds). “The stretch below Bullet has always been a tamarisk nightmare.”

We saw a lot of cattle on the mesa a few miles from highway. Did grazing contribute the “pasture weeds” now clogging the banks? “Wetherill complained about grazing in the Gulch in 1897,” Hadenfeld said. Rancher and amateur explorer, Richard Wetherill, made two expeditions to the Gulch excavating many ruins and removing many artifacts. Collins Trail, definitely built for horses, was constructed by ranchers for livestock access to the Gulch.

Although there are many personal accounts on Gulch hikes on Internet and the BLM offers information on archeology, we found nothing about natural changes. Some recent videos and news articles describe heavy flash flooding in southern Utah in 2013 and 2016; one hiker in 2004 said BLM rangers mentioned a 2003 flood and lake near Narrows. David thinks perhaps invasive non-native salt cedar in upper reaches of the Gulch caught and piled sediment from floods, creating the new deep channel. He noted some cottonwood trees with root base (exposed by erosion) many feet lower that current flood plain surface.

Many websites offer personal accounts hiking sections of the Gulch; many describe ruins and artifacts we did not see. Many hikers have used side canyons from the Gulch or even from the San Juan River, to loop back along the mellow table lands.

We used a Trails Illustrated Map (see below) that shows some of the famous ruins but does not name most canyons—including Shangri-La and others mentioned as good access to the rim by various hiker/bloggers. The BLM offers a crude map of the popular Kane-Bullet route with some ruins named but no guidance to find them—perhaps hoping to keep them “undisturbed.” (Most popular ruins have wire protecting sensitive areas, a marked access route and a register for visitors.) Visitors are issued a list of rules for protecting sites, disposing of human waste (dig a cat hole and pack out toilet paper), banning fires and bathing in the wash.

David spent considerable time reviewing websites before our trip; however we found that on this trip, like many other past hikes with marginal trip planning information, you almost have to do the hike first to decide on the questions. Then you can effectively search for “answers” from the plethora of amateur websites created to share an experience but not necessarily with the thought of providing helpful information to a broad spectrum of seekers.

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking right arrow down/up.)