Fire, Floods & Cow Pastures—Oh My!

We used to admire the Blue Range—a sprawling hunk of high-elevation wild country on the Arizona-New Mexico border—during our student days in Tucson. We often hiked the nearby and better known Gila Wilderness, and could see the “Blue” ridge upon ridge from Gila peaks only about 30 miles away.

It was on our bucket list in the 1970s. Too bad we never got there.

In 2011, we took a road trip from the Washington D.C. area back to our native West to visit favorite areas. We had planned a brief foray into the Blue Range Wilderness in New Mexico and perhaps further into the primitive area in Arizona. However, when we got to New Mexico, the only place not burning that we could visit was the west end of the Gila Wilderness—the Wallow Fire was already in progress. The Blue Range would have to wait.

The Wallow Fire, which jumped the highway into the Blue Range from adjacent Bear Wallow Wilderness, burned about 540,000 acres, forced evacuation in the town of Alpine and decimated most of the high elevation mixed-conifer forest that dominates the northwestern primitive area.

We finally got to the Blue Range Primitive Area in April 2017. Lacking good planning information, we unfortunately spent most of our time in the heavily burned northwest end where the Wallow Fire had left only remnant cienegas (Spanish for wet meadow) with few trees, only a little old-growth conifer and oak. Many trails were damaged or obliterated by fire. The east side of the river was nicer but dryer, with minimal water and lots more cattle.

Our trip began in unburned forest near Hannagan Meadows, but soon dropped into an area of green grass and tree skeletons—the most common sight throughout the high country. We found considerable old-growth ponderosa pine that survived the fire, in areas also often occupied by cattle.

Grey skies and rain showers dominated several evenings; otherwise, the weather was mostly pleasant with some chilly mornings. We had to plan carefully to work around limited dependable water on the east side. Trails were in fairly good condition except upper Foote Creek trail, which was washed out in the canyon and overgrown with brush on hillsides, and the trail in lower Grant Creek; also there were some down logs on ridges in the high country.

After our trip we did some reading on the area’s history and were surprised to learn that overuse of the Blue Range began 140 years ago, with altered vegetation and erosion that led to floods washing out Blue River Valley farms and perhaps setting the stage for catastrophic fire in the new millennium.

Blue Range Primitive Area in Arizona is the only national forest primitive area left in the United States not reclassified wilderness—most likely due to local politics. Local ranchers have consistently opposed wilderness designation of this 180,000-acre area.

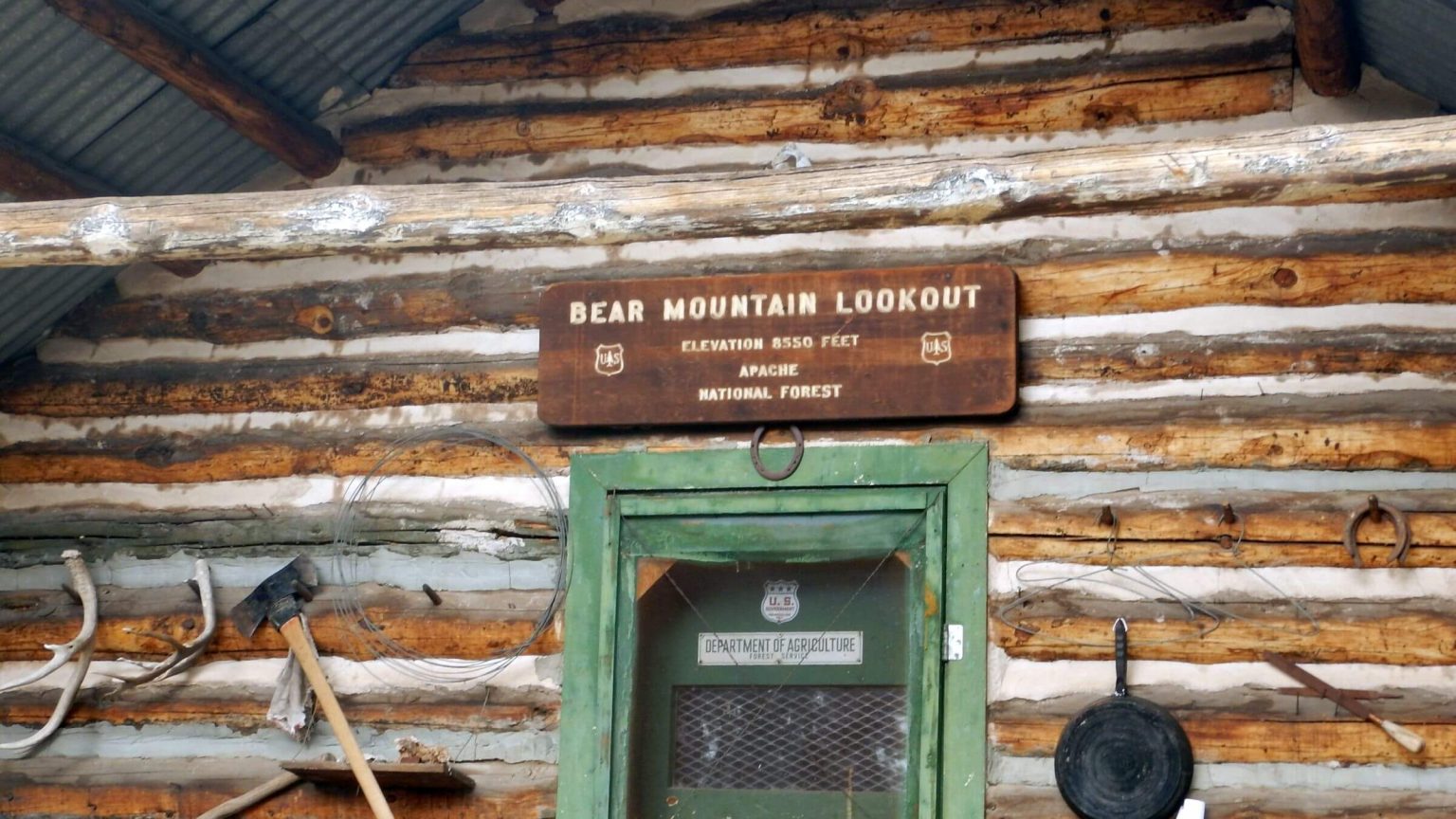

Our April 2017 visit to the northern half of the primitive area looped from Hannagan Meadows on the westside, descended highly burned cienegas (Spanish word for marsh or bog) and crossed the Blue River twice, once in a remote area and once in a community of private inholdings along Blue Road. Highlights were Bear Mountain lookout and nearby Devil’s Monument in New Mexico’s Blue Range Wilderness.

Wallow Fire of 2011, the largest fire in recent history in Arizona, severely damaged the northwest quarter of the Blue Range Primitive Area. The fire killed most of the high-elevation mixed-conifer forest on the western side and subsequent flooding scoured many streams and left rock heaps. Rolling ponderosa pine on the northeastern side fared better but that area is called—quite accurately—“pasture” by local cattle ranchers. Postfire hiking barriers included lost trails, down logs, and riparian canyons converted to boulder fields. Limited water, particularly on the eastside, offered additional challenge. (See kmz download).

Ecological demise of the Blue Range probably started much earlier, however; see the story for more.

Old-growth ponderosa pine were abundant on the eastside and some survived fire on ridges and in canyons on the westside. Periodic white-rock formations captivated our attention. We regretted not visiting this area before the Wallow Fire, ironically started by careless backpackers in the nearby Bear Wallow Wilderness.

Water availability varies and should be checked out in advance. We often use nearby U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) real-time gauging stations (found online) to judge area water availability. For example, the USGS station (see link below) on the Blue River 7 miles south of the primitive area boundary showed about 20 cubic feet per second flow (cfs) during our 2017 visit (about 5 cfs below normal).

Visit statistics: 8 days, 69 miles, and 450 feet per mile average elevation change. GPS records were lost so statistics were based on map data; we have no estimate of mph, but know it was slow going in burned areas.

See map below for trailheads, detailed daily routes, mileages, elevation changes, and photos.

show more

Settlement History

The Blue Range is a series of plateaus along the Blue River, which flows south from the Mogollon Rim to the Gila River. Remote, rough, and roamed by Apache Indian bands, the Blue Range did not attract white pioneers until the 1880s when Texas stockmen brought cattle to graze open (unregulated) range and farmers homesteaded on the river—a community of 300 by 1890.

Many early settlers had no formal land claim on these unclassified public lands, which became part of the Black Mesa Forest Reserve in 1897 and were transferred to the newly created Forest Service in 1905. Some Forest Service officials tried to evict the squatters but most eventually obtained a patent for 160-acre homesteads and a lease of federal grazing lands costing about 50 cents to $1 per acre per year (Stauder, 2009).

According to Jack Stauder (sociology and anthropology professor, University of Massachusetts) this overgrazing had devastating effects on the Blue River around the turn of the century. After settlers cut trees, plowed and planted crops, diverted flows for irrigation and grazed livestock in the area, a drought followed by wet years resulted in unprecedented flash flooding that washed away three-fourths of the once lush bottomlands and left a wide wash full of boulders. Many farmers left.

Conservationist Aldo Leopold was sent by the Forest Service to inspect the Blue Range in the 1920s and was the first to note possible ecological effects of overgrazing. He wrote his reflections on the Blue Range situation in an unpublished 1924 manuscript, later paraphrased in a book on the evolution of Leopold’s ideas on ecology (Flader, 1974).

In the late 1800s, there were vast summer grasses in the Southwest, often stirrup high. By the 1920s, grass had been replaced by vast brush fields and higher up, dense thickets of yellow pine. From fire scars in junipers 500 years old, not found after white settlement, Leopold saw indicators of periodic fire caused by lightning or set by Indians that lightly thinned brush and kept a mosaic of grass and trees. But overgrazing by hundreds of thousands of cattle and sheep thinned the grass which had carried fire, and it was replaced by brush and trees.

The Forest Service designated Blue Range as a primitive area in 1933 and recommended assigning wilderness status in 1971. Congress designated a Blue Range Wilderness in New Mexico in 1980 but never made the Arizona part wilderness; today it is the only national forest primitive area.

Our 2017 Visit

Almost 100 years after Aldo Leopold’s inspection, we found the Blue Range dry, still impacted by erosion and overgrazing, home to unfriendly in-holders, and further devastated by fire. We wondered if the dense forest Leopold saw starting in the 1920s had increased and helped fuel the Wallow Fire.

After two days hiking through the Wallow burn from Hannagan Meadows, we crossed the Blue River to find ponderosa pine and grass forest, less fire damage (from earlier fires as the Wallow Fire did not cross the river), and historic highlights such as Bear Mountain Lookout and Franz Cabin. We hiked into the Blue Range Wilderness in New Mexico to see the Devil’s Monument of soaring grey sandstone. We worked around limited water options for this part of the trip.

The biggest surprise occurred when we looped back to the Blue River on a national forest trail that abruptly ended up in someone’s backyard—one of several private properties in the unincorporated area of Blue River Valley. We passed a Forest Service sign reading Hinkle Spring and Bonanza Bill, where we had just come from. Beyond the sign was a wire gate, some buildings, and vehicles but no people. We continued down the road to a metal gate which we climbed over.

On the other side of gate was a sign with a gun pointing out and labeled “There is nothing here worth dying for.” Glad we missed this unhospitable landowner. Further investigation of a mailbox (marked “Gaddy”) indicated a long absence; several years of mail had accumulated. (The Forest Service online Recreation Map shows the Hinkle Trail #30 ending on private property but does not show any access problem. We might have done the trip differently had we known. After our camp near Franz Cabin, instead of backpacking to Hinkle Spring with a side trip to Devil’s Monument, we could have looped to the monument, then descended to Blue River on Lamphier Canyon Trail #52, which is shown as a trailhead across from Foote Creek.)

From the Gaddy property, we went around a bend and hiked through forest to the Blue River for a bath. I had zipped off my pant legs to cross the river and left them on a rock. Ants! Distracted, I forgot the pants legs and hiked up the road in my shorts—and remembered them that evening, far up Foote Creek Trail (which we accessed by hiking up Blue River Road). When hiking got rough, I hiked in rain pants until it got too hot.

Upper Foote Creek was a washed-out boulder field with ghost-white dead trees, down logs, brush, and a few remnant ponderosa pine. Little trail remained, but we saw cairns and fairly new flagging in spots. A hot hike across a rocky mesa of mostly burned mixed-conifer forest brought us back to our trailhead. We left with little desire to return.

Guess we’ll leave the northern Blue Range to the Blue River Valley in-holders and their cattle.

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking right arrow down/up.)