Steward Quit Job to Save Trails in Nation’s Oldest Wilderness

Six weeks backpacking in the Gila Wilderness in 2000 sealed a long-term commitment.

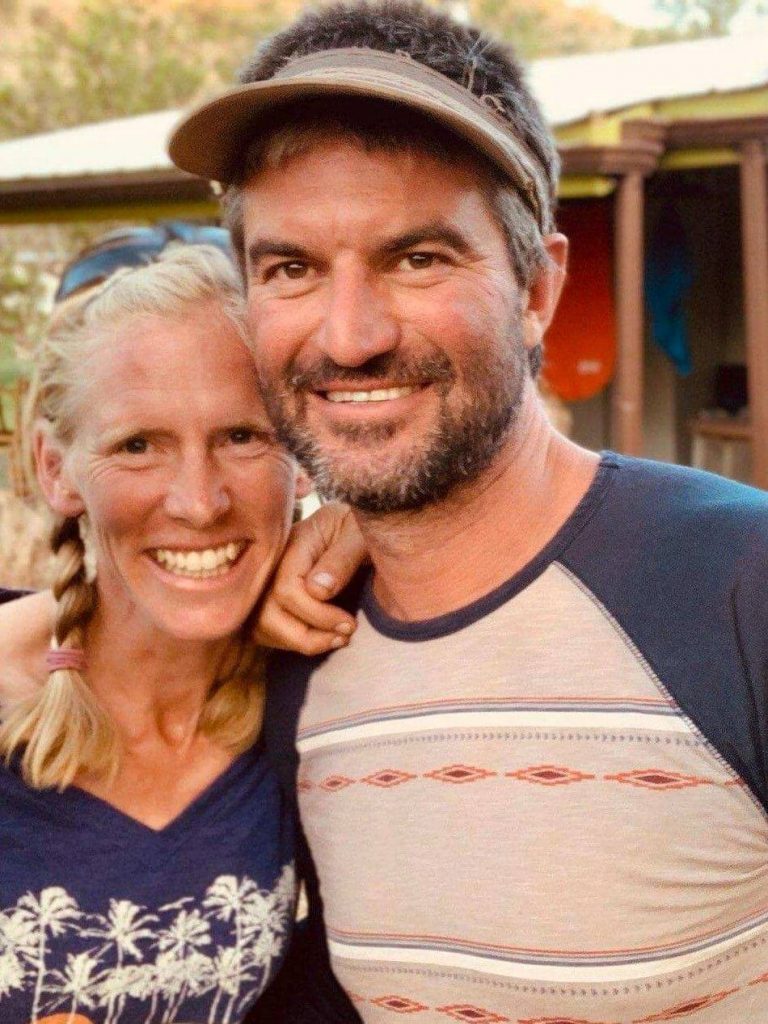

Melissa Green found a life purpose in the Gila, an extensive area of mountains, canyons, rolling ponderosa pine flats and parks, and dryland forest in southwestern New Mexico. She and husband Oliver have committed their lives and work to this wilderness, its vast system of legacy trails, and the public need to enjoy and experience this resource.

The Greens live out that purpose today. They built their own home in Gila Hot Springs, a hamlet on the Gila River surrounded by the vast wilderness and only a few miles from the nearest trailhead. They are the only year-round residents; accessing the area requires crossing the river, sometimes impossible in flood season.

“We have to keep 4 vehicles, I feel a little guilty about that,” Melissa says. Two heavy-duty trucks for crossing the river. Two more at Gila Hot Springs Resort up the road, where they sometimes have to hike a path and cross a foot bridge to leave for work.

Oliver is the facilities manager at the National Park Services Gila Cliff Dwellings Monument; Melissa divides her time between ranch work and massage to pay the bills and her true vocation: a Volunteer Trails Coordinator currently affiliated with Gila Backcountry Horsemen.

Melissa’s goal is to work with nonprofit organizations willing to support her vision of restoring the legacy trails of the Gila Wilderness. In her first two years shopping around for a trails partner, “I was surprised to find how few groups are interested in trails.”

This 558,000-acre Gila Wilderness is the country’s oldest, named wilderness by the Forest Service in 1924 on the urging of Aldo Leopold, the famous conservationist who spent much of his early career in New Mexico and had his famous encounter with a wolf in 1912 in the then unnamed Gila. Forty years later, the Gila was included in wilderness officially designated by Congress in the Wilderness Act of 1964.

Melissa brought 10 years’ trail work experience to her current vocation. After meeting at Prescott College in Arizona and working in youth wilderness therapy in Oregon, the Greens moved to Gila in 2008 to work on the forest’s Wilderness District seasonal trail crew. Melissa had worked seasonally on the Gila. Oliver eventually got a permanent job at the visitor center. The Park Service is supporting his initiative to develop new trails within Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and work on nearby national forest trails.

I met the Greens in 2015, around a backpacking trip. It was three years after the Whitewater Baldy Complex fire burned most of the wilderness, obliterated almost all the mixed-conifer forest at higher elevations and trashed the trails. Meeting a knowledgeable helpful federal official at the visitor center, I followed up later by email with specific questions on trails. “You have to talk to Melissa,” said Oliver Green, and a friendship was born.

John Kramer, recreation manager 30 years on the Wilderness District, which oversees most of this wilderness and adjacent Aldo Leopold, kept the trail crew running on grants for years . When he retired, the Gila National Forest began transitioning to a permanent, forest-wide trail crew. Melissa saw the handwriting on the wall. More funds were available for non-wilderness work; wilderness trails would continue to deteriorate. She jumped ship and found a non-profit to continue wilderness trail work, finding partner groups, state funding and grants to leverage trail restoration projects.

Some of her trail work in 2019 included:

- 3000+ volunteer hours;

- 50+ miles of trails maintained; including seven miles of the popular Middle Fork Gila River Trail with 47 cairns (rock piles to mark trail) built;

- 20+ trail junction signs made; 7 installed so far in places visitors have found confusing;

- 30 drains repaired or installed;

- 450+ logs removed from trails;

- trained volunteers at Gila Visitor Center to give accurate trail information; and

- helped direct 400 visitors during spring when flooding made some trails unsafe for use.

Besides the Gila horsemen, Melissa works with Continental Divide Trail Coalition, New Mexico Volunteers for the Outdoors, Gila Backcountry Services and other volunteers she recruits from around the country.

The task, she notes is huge. In a 2018 inventory of 490 miles of trail east of Mogollon Baldy, some 42 percent or 210 miles were damaged (not usable by stock, difficult to hike, not marked or signed or obliterated by floods). About 75 miles of trail were repaired by volunteers or the Forest Service. More miles were restored this year but “there is much left to do.”

The inventory skipped trails west of the Mogollons on the Whitewater creeks (Glenwood District) because many were completely destroyed and too costly to reopen or it’s prudent to wait several years until most burned trees have fallen.

Even on passable trails, post fire trail maintenance is a moving target. Trees fall for many years, blocking trails. Post-fire vegetation grows like gangbusters, clogging trails with grasses and Mexican locust. Moonscape high mountains contribute floods for years to come, scouring river and creek beds and damaging trails.

“I would like to see the trails open along different access points to increase visitor opportunity for solitude and reduce impact on the wilderness.” Melissa freely admits volunteers can’t do it alone. “We really need the help and cooperation of the Forest Service.”

John Kramer, Melissa’s former boss during her trail crew days, has absolute confidence in her competence and trail savvy. “She knows that trail system. She knows what to do. You can send her out without any instructions.” He shared a story about Melissa using “pyramid building techniques,” moving a huge boulder downslope to position it where needed on trail below by using a pulley and small pine logs she had cut out to serve as rollers.

“Melissa is a in a good position to lead the non-government volunteer trail effort. She knows the area, she knows the trails, she has years of experience.”

Melissa and Oliver provided invaluable information and review help for Bill and Polly Cunningham, authors of a Gila Wilderness hiking guide and former outfitters in the Gila Wilderness. Their book Hiking New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness mentioned the Greens in its Acknowledgements section: “They live near Gila Hot Springs in a unique open-air home they built. They’ve both worked on the Forest Service trail crew for nearly a decade, so they know first-hand the condition of trails and the timeless rhythm of the wilderness.”

Describing Melissa, Polly Cunningham adds, “her heart is totally into the stewardship of this incredible area.”