Volunteer Does Wilderness Ranger Work Across the Country…

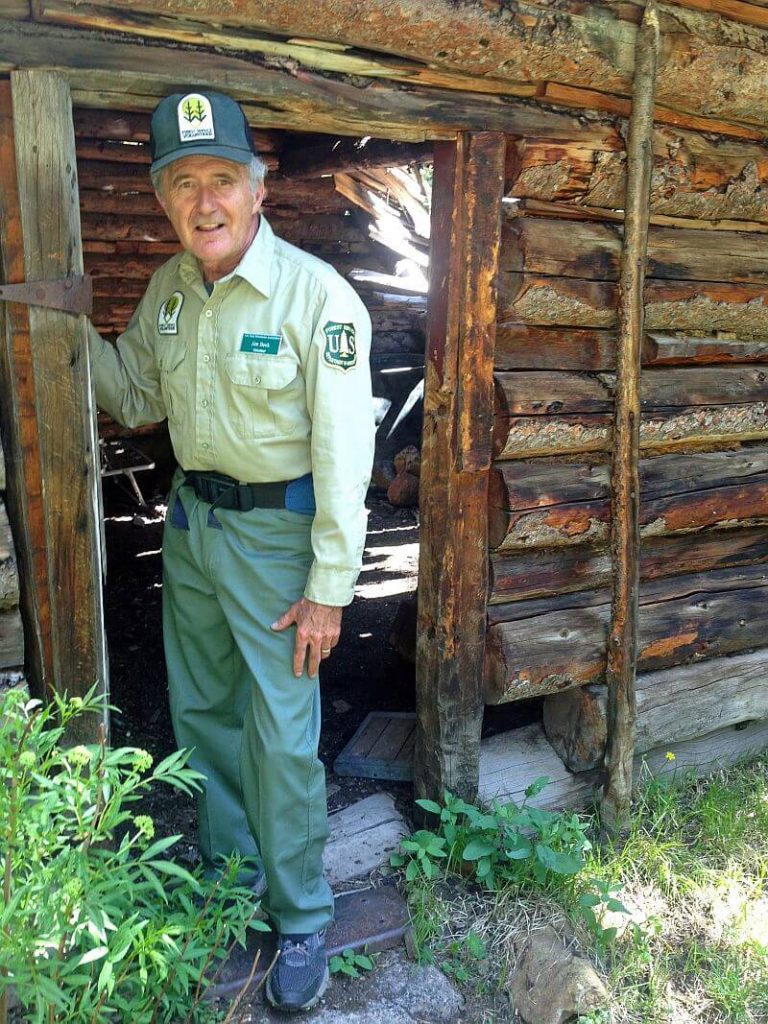

Jim Beck took “early retirement” in his late 50s but started a new career—hiking, climbing, clearing trails and doing stewardship work across the country. He’s a volunteer.

In 2016 Beck, a former consultant whose resume now reads “Outdoor Volunteer,” hiked 250 miles of trail in the rugged Superstition Wilderness in Arizona to locate trail signs for the Mesa Ranger District, Tonto National Forest.

“We ended up in Arizona … and I showed up on the Mesa district doorstep. I said ‘I’m in town, I want to volunteer and I’m highly qualified,” Beck said. He walked out that day with a uniform. “Turns out they don’t have any staff assigned to the Superstition Wilderness.” Beck located 34 old signs; many were subsequently replaced by the Forest Service throughout the west side of the sprawling 160,236-acre urban wilderness at the edge of Phoenix. He also hiked virtually abandoned trails on the obscure eastside of the wilderness to provide trail condition reports to district managers, who applying for grants for needed trail work.

Jim’s first ‘job’ was wilderness ranger in the Boundary Water Wilderness in Minnesota. This notion had caught Jim and his wife Cathy’s interest when both were still working full time. During a “trip of a life time” canoeing in Boundary Waters, Beck talked with an outfitter who said his post-retirement dream was a volunteer ranger slot. “They have a cabin back in the wilderness, people go out there and stay, check on campsites, talk to people…That stuck in my head for years and years. I said, ‘I’m going to do that.’ He got in touch with the Superior National Forest and snagged a volunteer ranger job—not in the remote cabin, by then defunct.

The next summer, Beck showed up at Pagosa Springs Ranger District in Colorado, snagging a post as volunteer ranger in the Weminuche Wilderness. Beck, who has climbed all the 14,000-foot peaks in Colorado, patrolled Chicago Basin, a favorite access point for peak-bagging climbers, and also used his cross-cut sawyer skills to clear trails.

Next project was the Superstitions, then a Nature Conservancy Project in the Florida Keys, and back to Arizona to help improve trails in Mount Wrightson Wilderness near the Arizona border.

The Becks have a permanent address in Alaska but have been living in their motor home, exploring areas and doing projects that appeal to their love of the outdoors. After both retired early, they sold their home in Evergreen Colorado, bought the motor home and visited all states (49) that can be driven to. The volunteer projects offer new travel focus.

“It was my desire to give something back,” said Beck. “I have felt very privileged to have spent all these years immersed in the glory of nature and felt I should pay forward for that experience.”

Future options includes Teton National Park in Wyoming and Denali in Alaska. “I’m really interested in wilderness,” he said. “My plan is to continue to seek out new adventures…go from place to place and continue this as long as I can.”

“The sands are running in my hourglass,” said Beck, 67. “But I am happy to say that so far I am able to kick butt on the desk jockeys.”

Beck was surprised that the Superstitions, highly used by metropolitan Phoenix (5 million in greater Maricopa county) has no Forest Services staff assigned. (The Tonto National Forest, claims 5.8 million visitors a year and heavy recreation workload with ATVs, floaters on the Salt River, boaters and motorists, equestrians and hikers).

So the public is assuming some of the workload in the Superstitions. “There are volunteers at popular trailheads spending the morning talking to users going in…to keep people out of trouble. And now thanks to some of the key (volunteer) people, they have volunteer groups adopting trails. None of it is being done by paid staff.”

In the more remote eastside backcountry, Beck even found trail clearing work done by unknown parties, a surprise to the Forest Service. If no one uses a trail, the manzanita, cat claw and other thorny vegetation take over and trails become impassable. “I still have some scars from the cat claw.”

VOLUNTEERING: As domestic federal budgets have declined in real dollars over the past few years, resource agencies such as the USDA Forest Service, National Park Service (NPS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) have increasingly relied on volunteers for research support, wilderness patrols and public contacts. We used to say “real work” was done by seasonal employees; now it’s largely volunteers. Agencies don’t pay salary, but often provide minimal reimbursement for expenses such as transportation, food, lodging and miscellaneous expenses. Uniforms, tools and vehicle are often supplied to support the work project. For more details, check out volunteer information on-line (https://www.volunteer.gov/ for NPS, BLM and FWS and https://www.fs.fed.us/working-with-us/volunteers for the Forest Service).